‘The Serious and the Smirk’

Nicholas Jeeves

An essay exploring the history of the smile through the ages of portraiture, from Leonardo’s Mona Lisa to Alexander Gardner’s photographs of Abraham Lincoln.

First published in The Public Domain Review, October 2013; and later in The Public Domain Review: Selected Essays, The Best of the First Three Years, 2011-2013 (PDR Press, 2014).

In Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39), the portrait painter Miss La Creevy ponders a problem:

People are so dissatisfied and unreasonable, that, nine times out of ten, there’s no pleasure in painting them. Sometimes they say, ‘Oh, how very serious you have made me look, Miss La Creevy!’ and at others, ‘La, Miss La Creevy, how very smirking!’… In fact, there are only two styles of portrait painting; the serious and the smirk; and we always use the serious for professional people (except actors sometimes), and the smirk for private ladies and gentlemen who don’t care so much about looking clever.

A walk around any public art gallery will confirm the truth in Miss La Creevy’s words: among the portraits there are the serious, and there are the smirks. But the one expression you will almost never see is the open smile.

While a smile in life is usually welcome, the smile in art has long been largely, as it were, frowned upon. The most obvious reason for this, and the one most commonly given, is a practical one: that an open smile is hard for the sitter to hold, and therefore hard for the painter to paint. This is something all of us have experienced for ourselves to some degree: when a camera is produced and we are asked to smile, we do so willingly — but should the process start to take too long, it takes only a fraction of a moment for our smiles to turn into awkward, unpleasant grimaces.

A smile, then, is like a blush — it is a response, not an expression per se, so cannot be easily maintained nor easily captured in paint. But perhaps there are other reasons for the absence of smiles in portraiture beyond the practical challenges.

The primary reason concerns what an artist might be trying to do. While an open smile is unequivocal — a signal moment of unselfconsciousness — for an artist, the serious or the smirk are preferable in that they may convey almost anything. From piqued interest, condescension, flirtation or wistfulness to boredom, discomfort, contentment, or mild embarrassment, such a variety of possible readings allows the artist to offer us something the open smile cannot: almost limitless ambiguity, and thus an opportunity for us to forge an ongoing and lasting relationship with the portrait as a work of art.

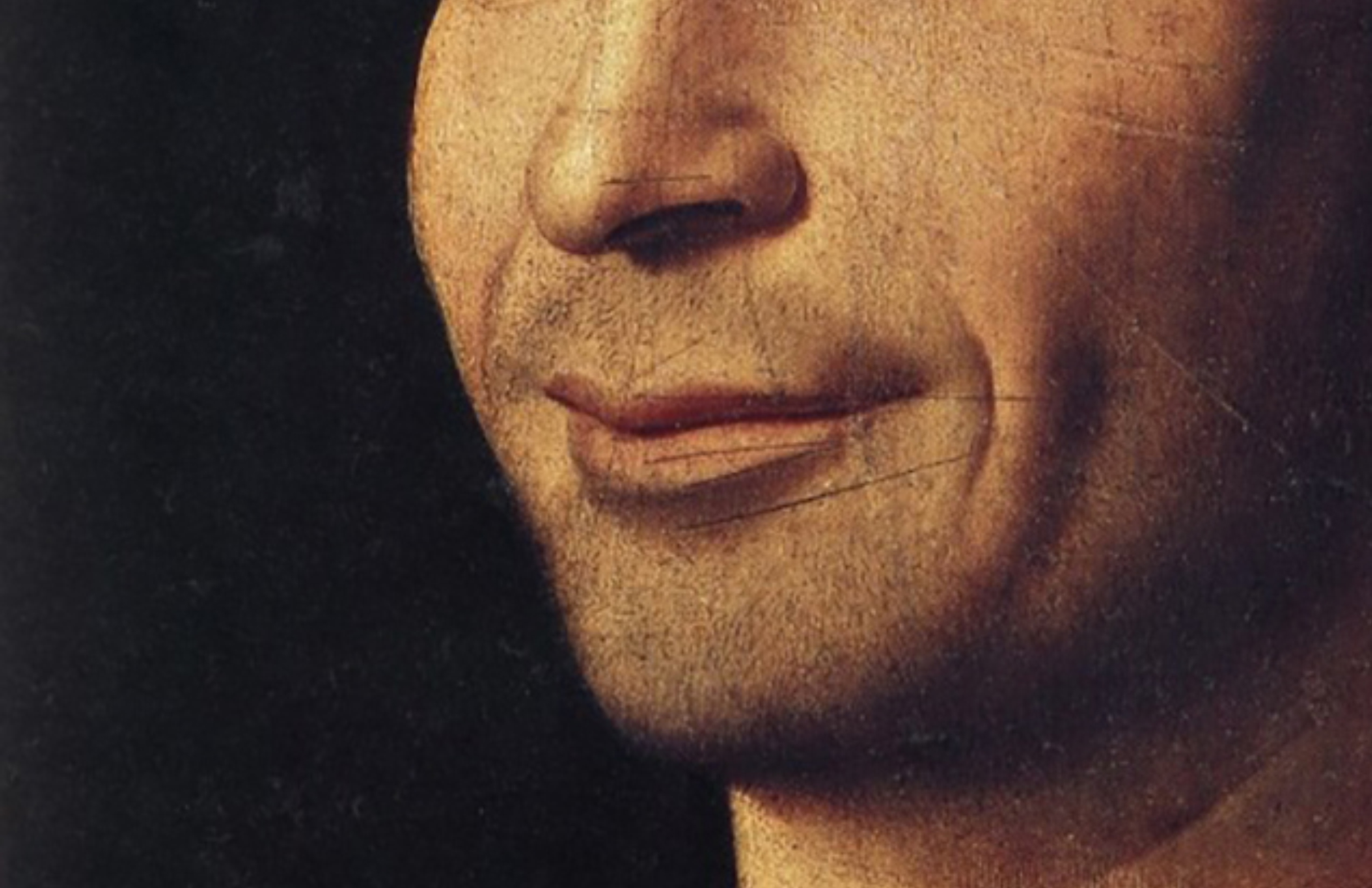

The most famous portrait in the world works around this very principle. Millions of words have been devoted to the Mona Lisa and her smirk — more generously known as her ‘enigmatic smile’ — and so today it’s difficult to write about her without sensing that you’re at the back of a very long and noisy queue that stretches all the way back to sixteenth-century Florence. But the effect of this most famous of portraits has always been in its inherent ability to demand further examination: when you first glimpse her, she appears to be issuing an invitation, so alive is the smile. But when you focus your attentions and the sfumato — the smoky effect Leonardo has given to his canvas — starts to clear, she seems to have changed her mind about you, and she is now looking away, distant and unreadable. This is interactive stuff, and paradoxical: she is only really there when you’re not really looking.

The most famous smile – or smirk – in the world, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, known in Italian as La Gioconda. The name itself is intended to raise a smile: La Gioconda literally translates as ‘the jocund one’ – a pun on the feminine form of the sitter’s married name Giocondo.

The Mona Lisa’s smile seems, then, specifically designed to frustrate. And frustrate she has. One critic and historian in particular, Jules Michelet, enjoyed, or at least endured, a very personal moment with her. In Volume VII of his Histoire de France (1855) he wrote, ‘This canvas attracts me, calls me, invades me. I go to it in spite of myself, like the bird to the serpent.’ An early expression of the new cult of the Mona Lisa, and over the years historians would attempt to outdo each other with their devotion to her charms. Michelet’s son-in-law Alfred Dumesnil, also a critic, went even further in his L’art Italien, as if locking antlers with his in-law: ‘The smile is full of attraction, but it is the treacherous attraction of a sick soul that renders sickness. This so soft a look, but avid like the sea, devours.’ In England, John Ruskin asserted that it was a merely a ‘caricature’, to which a young Oxford don named Walter Pater responded in his 1873 book Renaissance: ‘All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there… the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias…’

And so the discussions continue to this day.

Another commonly held belief about the smile is that, historically, people were reluctant to reveal their teeth due to them being in a generally awful condition. This is not really true — bad teeth were so common that this was not seen as necessarily taking away from someone’s attractiveness. (Lord Palmerston, Queen Victoria’s whig prime minister, was often described as being devastatingly good-looking, and having a ‘strikingly handsome face and figure’ despite the fact that he had a number of prominent teeth missing as a result of hunting accidents.) Rather, smiling has had a large number of discrete cultural and historical significances, few of them in line with our modern perceptions of it being a physical signal of warmth, enjoyment, or even happiness. In seventeenth-century Europe it was a reasonably well-established idea that an excessive showing of the teeth was, for the upper classes — who were, after all, paying for these portraits — something of a breach of etiquette. St Jean-Baptiste De La Salle, in The Rules of Christian Decorum and Civility of 1703, wrote:

There are some people who raise their upper lip so high... that their teeth are almost entirely visible. This is entirely contradictory to decorum, which forbids you to allow your teeth to be uncovered, since nature gave us lips to conceal them.

We may take such statements with a pinch of salt, it being self-evident that, in private at least, the upper classes would have enjoyed a laugh as much as anyone. Still, after centuries of tradition, should a painter have persuaded his sitter to hold a smile, and then chosen to paint it, it would immediately have radicalised the portrait precisely because it would have been so unconventional. Suddenly the picture would have been ‘about’ the open smile, and this is almost never what an artist — or indeed a paying subject — wanted. In this sense a portrait was never so much a record of a person’s true character as a formalised ideal. The ambition was not to capture a moment, but to effect a lasting moral certainty.

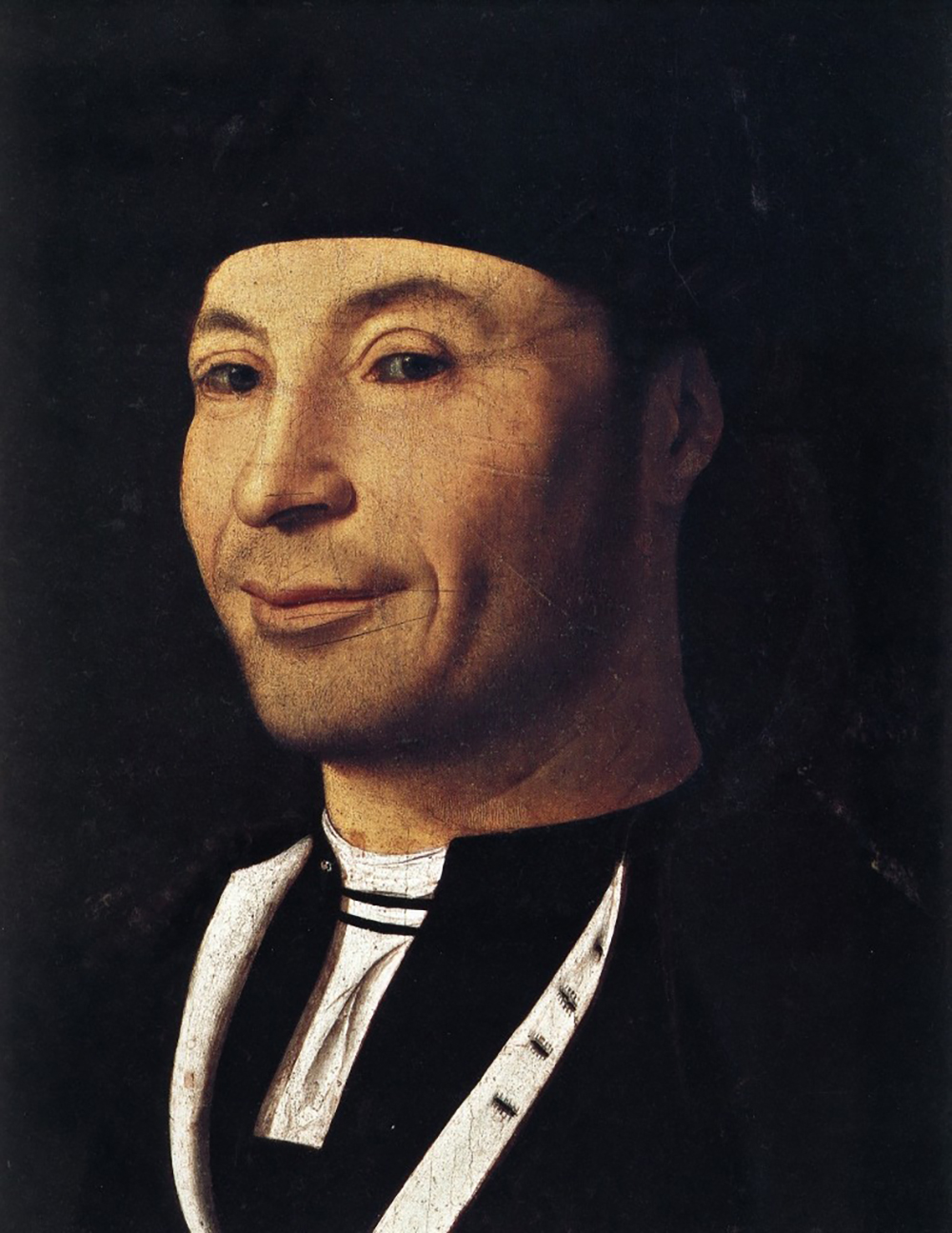

Yet the open smile had been attempted. As far back as the late 1460s, Sicily’s Antonello da Messina tackled it when he painted what we now know as Portrait of a Man (one of many Antonello portraits of unknown sitters). Antonello painted quite a few portraits with smiles, and the subject seemed to interest him. He doesn’t go quite so far as to show the teeth in Portrait of a Man, but does goes give him long dimples on his cheeks and laughter lines at the corners of his eyes. The teeth, we feel, are but a moment away. Unfortunately, this has the effect of making him look less, rather than more, human. The tension between the static quality of paint and the suspended animation of the smile confuses us, so much so that we are presented with a facial expression that is unnervingly unreadable. It is ugly in a way that is hard to describe — it is just repulsively ‘other’ — though some people still think it beautiful, and the unknown Man himself must at least have been reasonably satisfied.

Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man, c. 1475.

Better-known artists also flirted with the smile. Caravaggio’s Triumphant Eros of 1602 was designed as a meditation on adolescent beauty, and as such is not strictly portraiture. Indeed, so wild and voracious was the boy’s smile that it was typically read at the time as a scandalous celebration of sexual passion. In the picture, all the instruments of civilised society have been turned over in the face of all-consuming love — but his wicked smile speaks of lust. It may seem extraordinary to us today that the open smile was perceived as being the most pointedly shocking aspect of the picture despite Eros’ childishly displayed sex. Caravaggio, a born rebel with sociopathic tendencies, no doubt revelled in the scandal.

Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia (Triumphant Eros), 1602.

In more modern times, John Singer Sargent, in his 1890 study for Miss Eleanor Brooks, draws his subject with a smile that manages to be both truly warm and civilised. Despite this, he later rejected it in favour of a more composed expression in the final work, clearly dissatisfied with the results of the study. As he himself put it, “A portrait is a picture of a person with something wrong with the mouth.”

Left: John Singer Sargent, study for Miss Eleanor Brooks, 1890; Right: John Singer Sargent, Miss Eleanor Brooks (detail), 1890.

But to see the smile at its biggest and best, we have to leave the upper classes and instead visit our attentions on the masses. In seventeenth-century Holland a trend emerged among painters for recording life in the round, and many deliberately sought out the smiles they found there. Here there are almost no end of artists to choose from. Jan Steen, Frans Hals and Judith Leyster were all followers of this approach, all painted broad smiles, and — perhaps most tellingly — all were said to be good company.

Left: Jan Steen, Self-Portrait Playing the Lute (detail) ca. 1663. Right: Judith Leyster, The Jolly Toper, 1629.

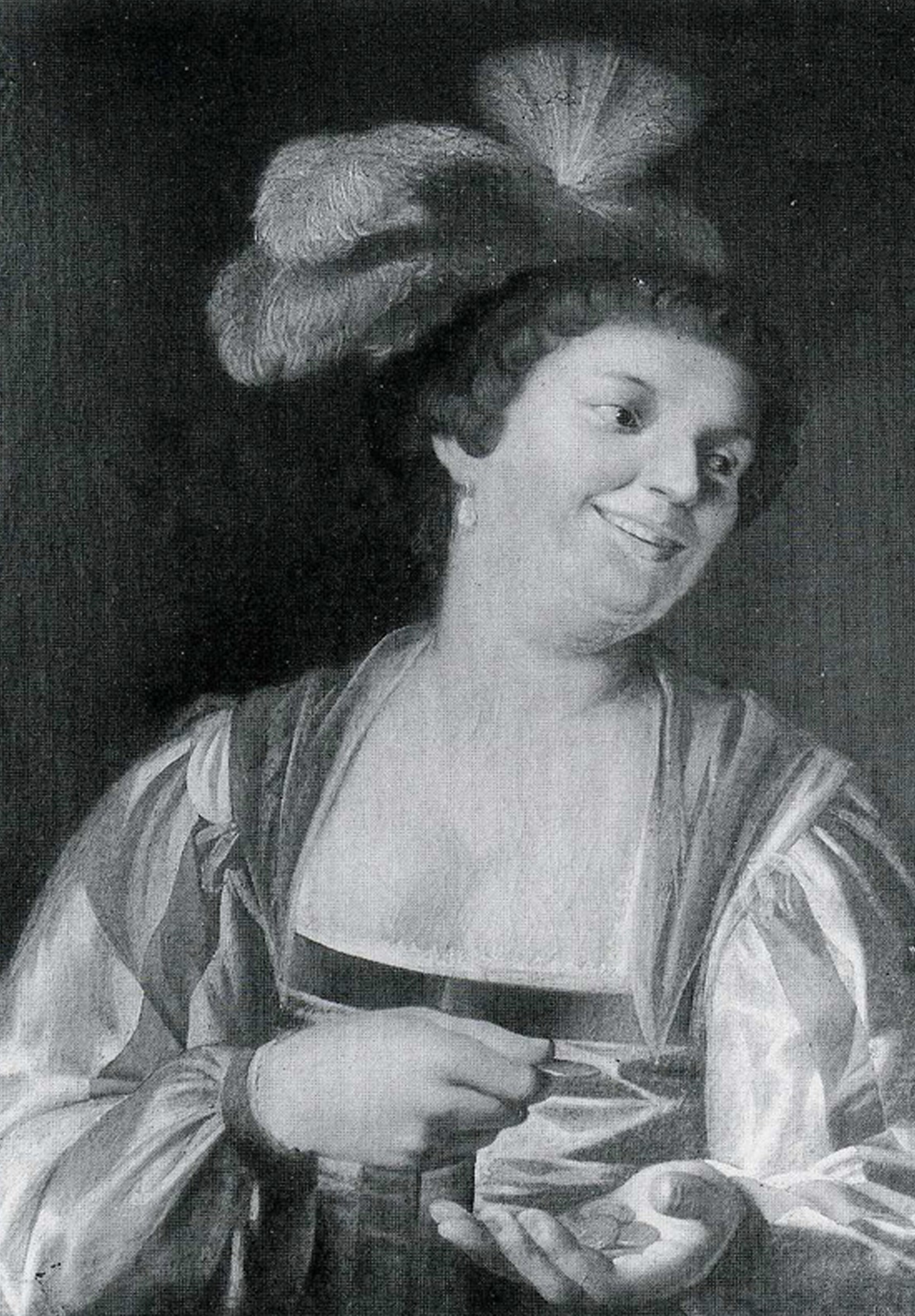

Possibly the most ambitious of these was Gerrit van Honthorst. Having seen Caravaggio’s work in Italy, Honthorst was so taken with him that he made every effort to channel his style, particularly with his mastery of chiaroscuro. He immediately saw in Caravaggio something real and worthwhile, and sped back to Utrecht to record his own high-voltage scenes of late-night eating, drinking and music-making in thrilling detail.

A terrific example of the life and low-life that he sought to represent is The Laughing Violinist of 1624. Since the Renaissance, any reference to music in painting was usually interpreted as a symbol of love. Honthorst, again inspired by Caravaggio, wanted to go much further, with sexual overtones so explicit as to break new ground. And so his laughing violinist not only has a lewd expression and almost audible laugh, but is making a universally understood hand gesture. What is quite brilliant about the painting is that, on its own, it crashes through the boundaries of taste with sheer accomplishment (just as Caravaggio’s paintings did). But when it is hung as intended, immediately to the right of his portrait Girl Counting Money, it becomes clear who the jeer is aimed at. Honthorst cracks the issue of the open smile by ensuring that we see it as it exists — not as an expression at all, but as a reaction.

Left: Gerrit van Honthorst, Girl Counting Money, 1623. Right: Gerrit van Honthorst, The Laughing Violinist, 1624.

Such a relaxed attitude towards the humour of everyday life never really caught on in societies where a more protective attitude to class prevailed. England’s William Hogarth was very interested in the smile and its impact on beauty. In his Analysis of Beauty he approved of the lines that ‘form a pleasing smile about the corners of the mouth’, but loathed a face in extreme contour, considering it ‘a silly or disagreeable look’. In his own work he saved it almost exclusively for depicting the drunken, corrupted poor.

William Hogarth, A Harlot’s Progress, Plate 4, 1732.

By 1877 the photographic pioneer Eadweard Muybridge had solved the problem of fleeting movement with his series of photographs entitled ‘The Horse In Motion’. As we know from artists’ previous attempts to paint running horses, the animal’s movements had been difficult to capture accurately in paint. Thanks to Muybridge’s pictures, painted horses were transformed from awkward caricatures into great galloping beasts virtually overnight — and before you could say ‘cheese’, photographers, and therefore painters happy to work from photographs, found themselves able to capture another fleeting thing: the true smile.

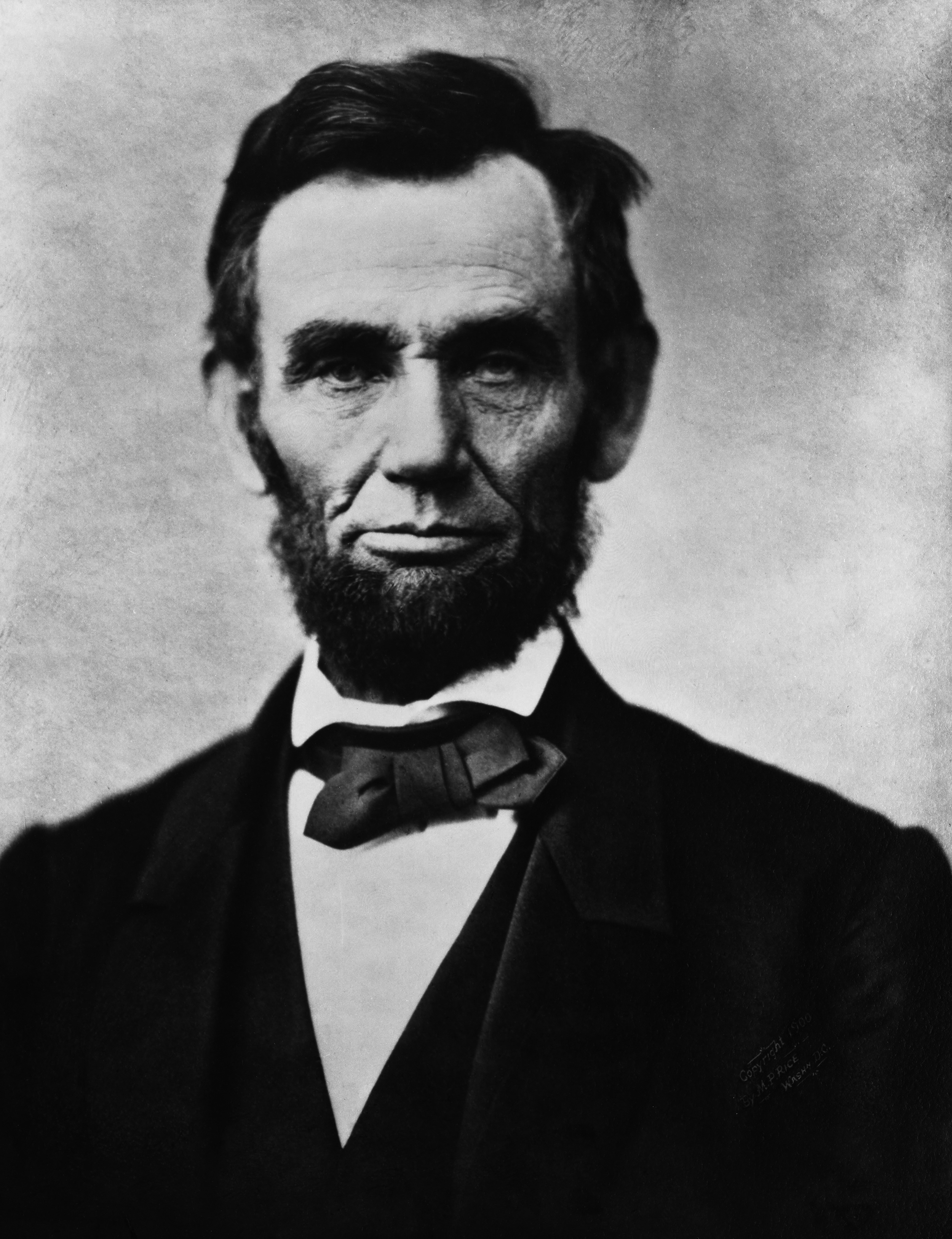

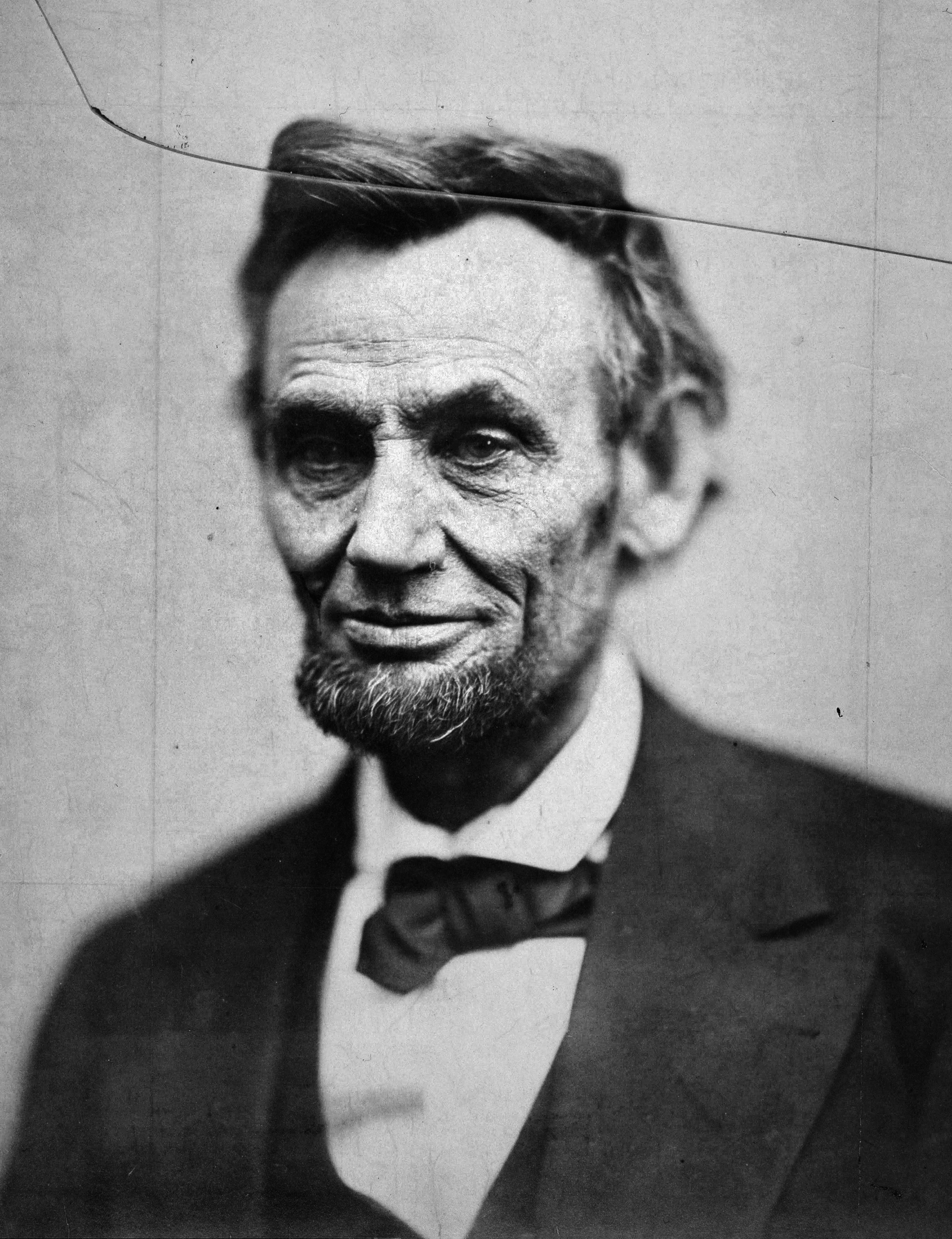

Yet despite the problem of sitting with a smile now pretty much resolved, many sitters were still tentative about the idea, particularly if they were public figures. Abraham Lincoln was a man better known than most, in his day, for his sense of humour, there being a number of well-known stories about him regularly drawing howls of laughter from those in his company. Yet in his best-known image, the ‘Gettysburg portrait’ taken by Alexander Gardner, he is recorded with the gravest expression he can muster.

Left: Alexander Gardner’s official photograph of Abraham Lincoln which came to be known as the “Gettysburg portrait”. Right: A later, less formal portrait of Lincoln by Gardner, revealing something of his reputed natural warmth and humour.

It was perhaps an appropriate pose to strike considering the solmenity of the occasion it marked, but so powerful are these images that this is how he is generally remembered today (although there are one or two photographs that give us something more of the true man).

Mark Twain, a contemporary of Lincoln’s, was firm on the matter in a letter to the Sacramento Daily Union:

A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.

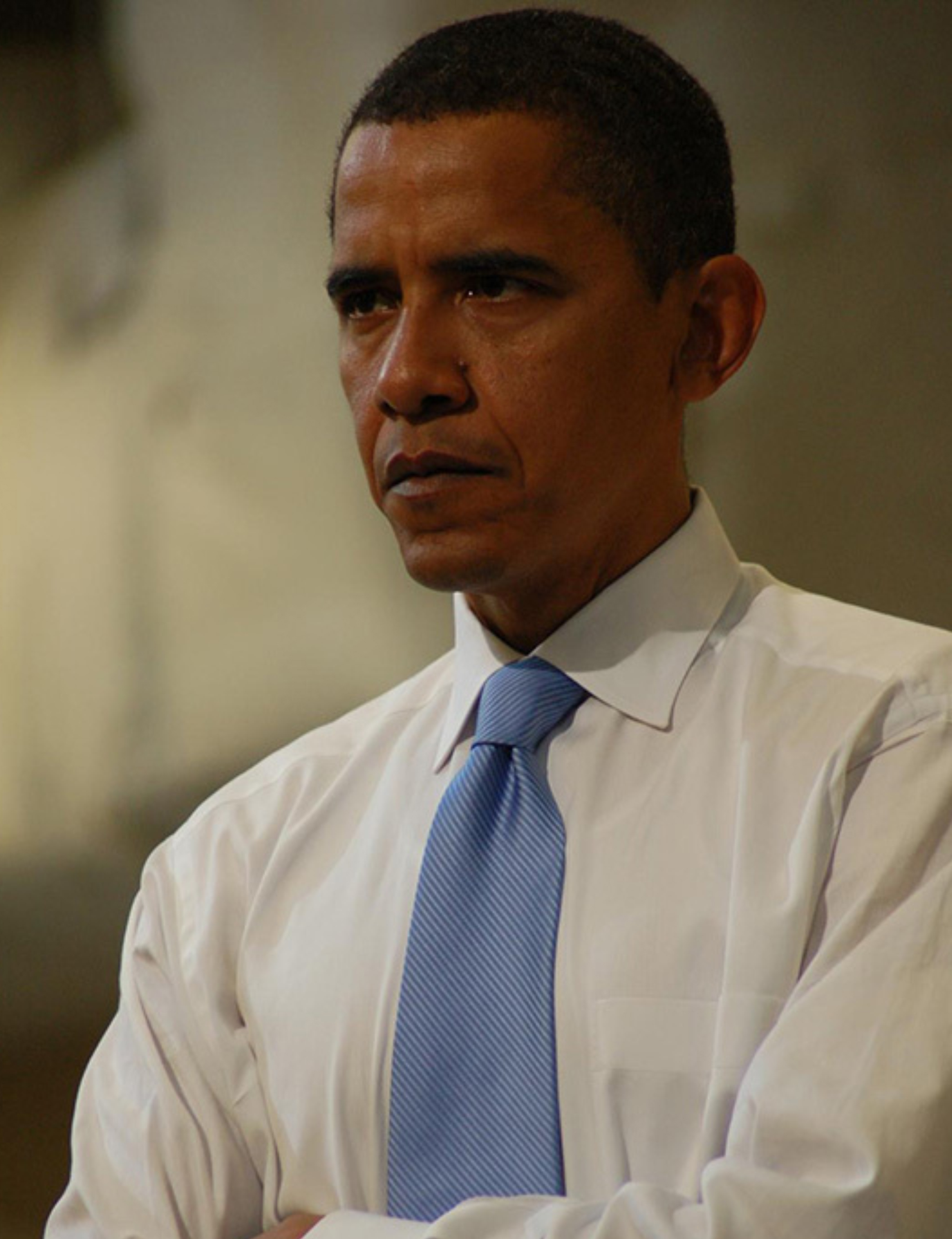

But nowadays each of us has a camera and in consequence is recorded across hundreds, often thousands of images, and in a great many of them we will be smiling. The photographic portrait is no longer ‘a most important document’, directing posterity. Indeed, unlike Abraham Lincoln, modern US presidents make available innumerable photographs that collectively serve to capture the totality of their emotional range, from troubled solemnity to enthusiastic joy. The same goes for royal families, celebrities, and anyone else who believes they have a professional image to manage. In the twenty-first century these figures must, and now may, be all things to all people.

Left: Pete Souza, President Barack Obama, 2012. Right: Elizabeth Cromwell, President Barack Obama, 2007.