Spring Sessions

Nicholas Jeeves

The Spring Sessions is a cross-disciplinary programme of artists’ talks, seminars, workshops, walks, dinners and screenings held annually in Amman, Jordan. I attended in 2014; this text is adapted from my diary, later published in the Spring Sessions Journal.

The Spring Sessions is a communal learning experience and arts residency programme held in Amman, Jordan. Bringing together creative practitioners to create a body of cultural knowledge, the program’s mission is to facilitate dialogue between emerging and more established cultural practitioners.

The program consists of workshops, lectures, seminars, artist talks, walks, dinners and film screenings. These offer the participants a cross-disciplinary view on topics that consider the participants’ diverse backgrounds and prompt the group to reflect on elements of our behaviour and daily experiences.

For the session I led, entitled ‘Imagined Worlds in Text and Image’, participants were tasked with generating artefacts from an imaginary culture. The artefacts were then recorded in a catalogue of fragments that, in their totality, begin to build a picture of the people, places and customs of these fictional societies.

︎

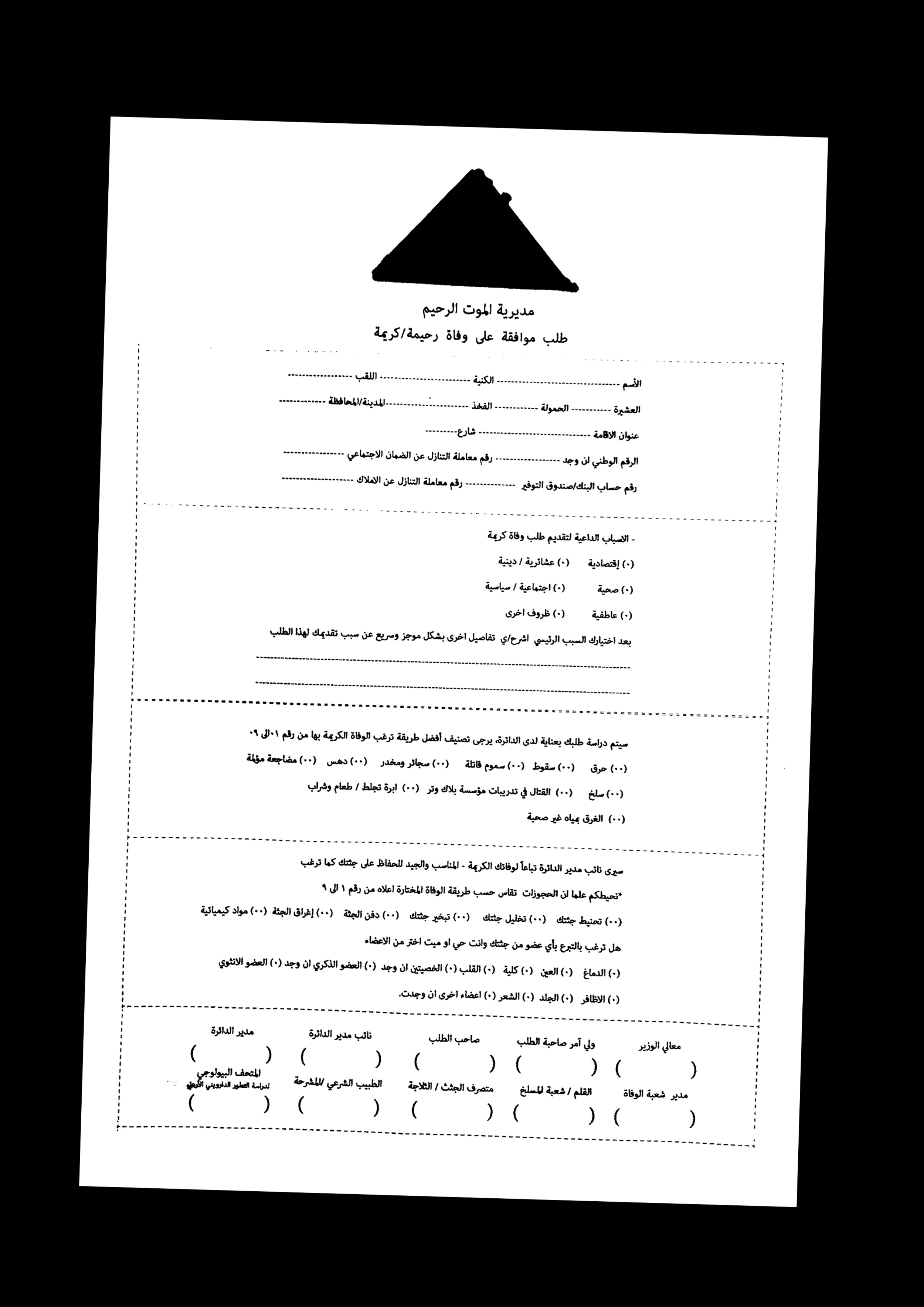

It is 6pm on the second day of the Spring Sessions and I'm talking to Laith. He is showing me a piece of paper that looks like an official form of some kind, headed with a governmental seal and underneath a long list of fields to fill in.

‘It’s an application for death,’ he says. ‘You put your name and address here, the reason you are applying here, your sponsor’s signature here, and’ — he draws a finger down the page — ‘here you get to choose the manner of your death: Firing Squad, Poison, Drowning, Other.’

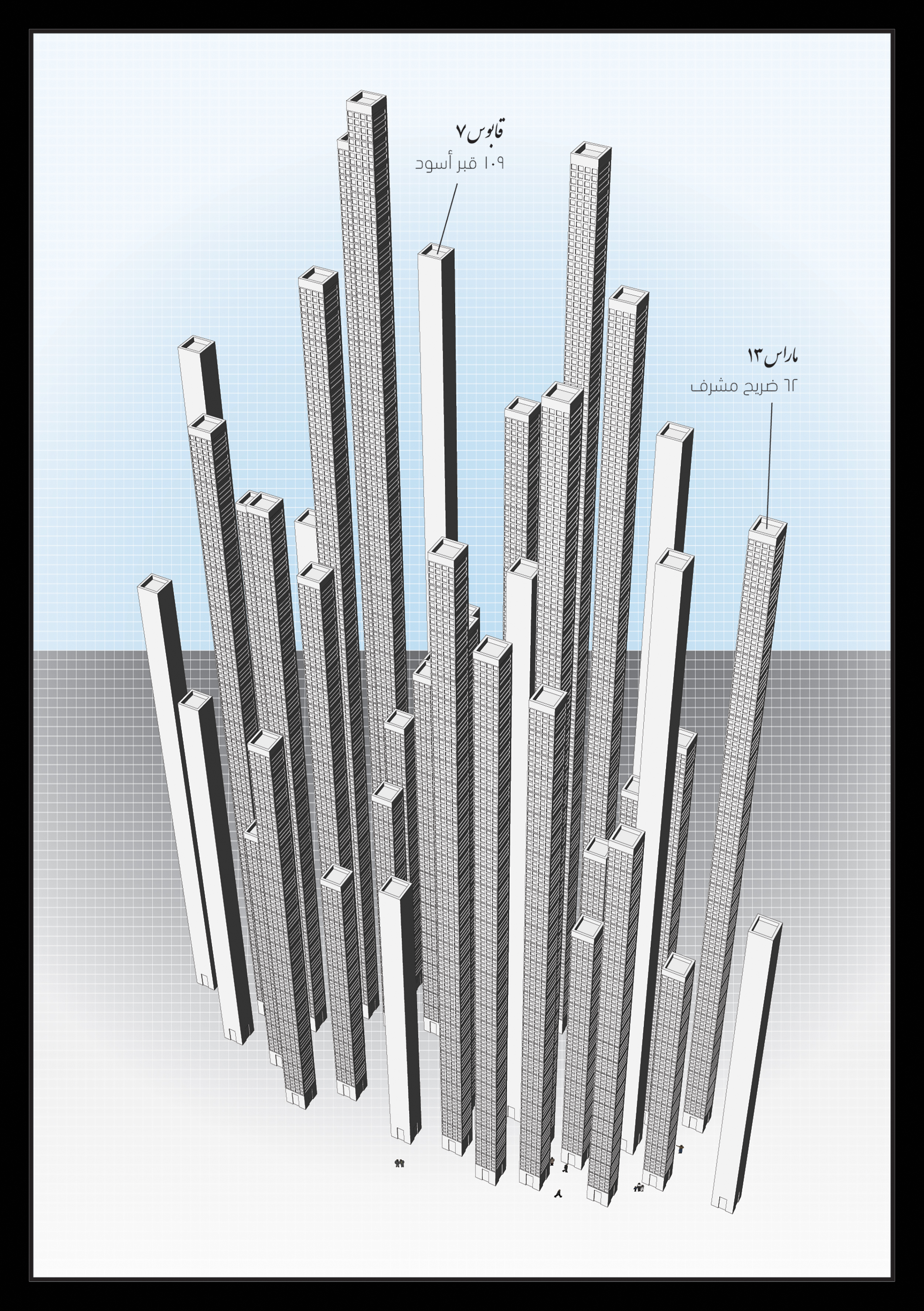

It is testament to the spirit of the Spring Sessions that a ripple of excited giggles passes through the room. With each participant having been charged with creating a fragment from an imaginary society, already we have seen several expressions of a nervous preoccupation with death rituals. So far Rola has proposed a propaganda poster that encourages militant cannibalism (’Eat Human. Eat Right’). Noura is creating an architectural plan for ‘Khora, an infinitely vertical graveyard.’

Left: ‘Facsimile of an official application for death.’ (Laith / Mahmoud). Right: ‘Plans for Khora, the world’s tallest cemetery, comprising 34 Maras, 9 Qabus and a total of 2798 graves stacked over an area just shy of one acre.’ (Noura Salem).

Shareen has an idea for an uninterrupted stream of messiahs, ’Each one betrayed and executed in rotation as part of a continual spiritual system’. And Rana has imagined a society in which narcissism is a capital crime, and in which the penalty for seeing one’s self in a photograph is death. Mirrors are banned.

‘I’m not going to this place for a holiday,’ says Suzanne, and there are more nervous laughs.

Discussing proposed artefacts with Spring Sessions participants.

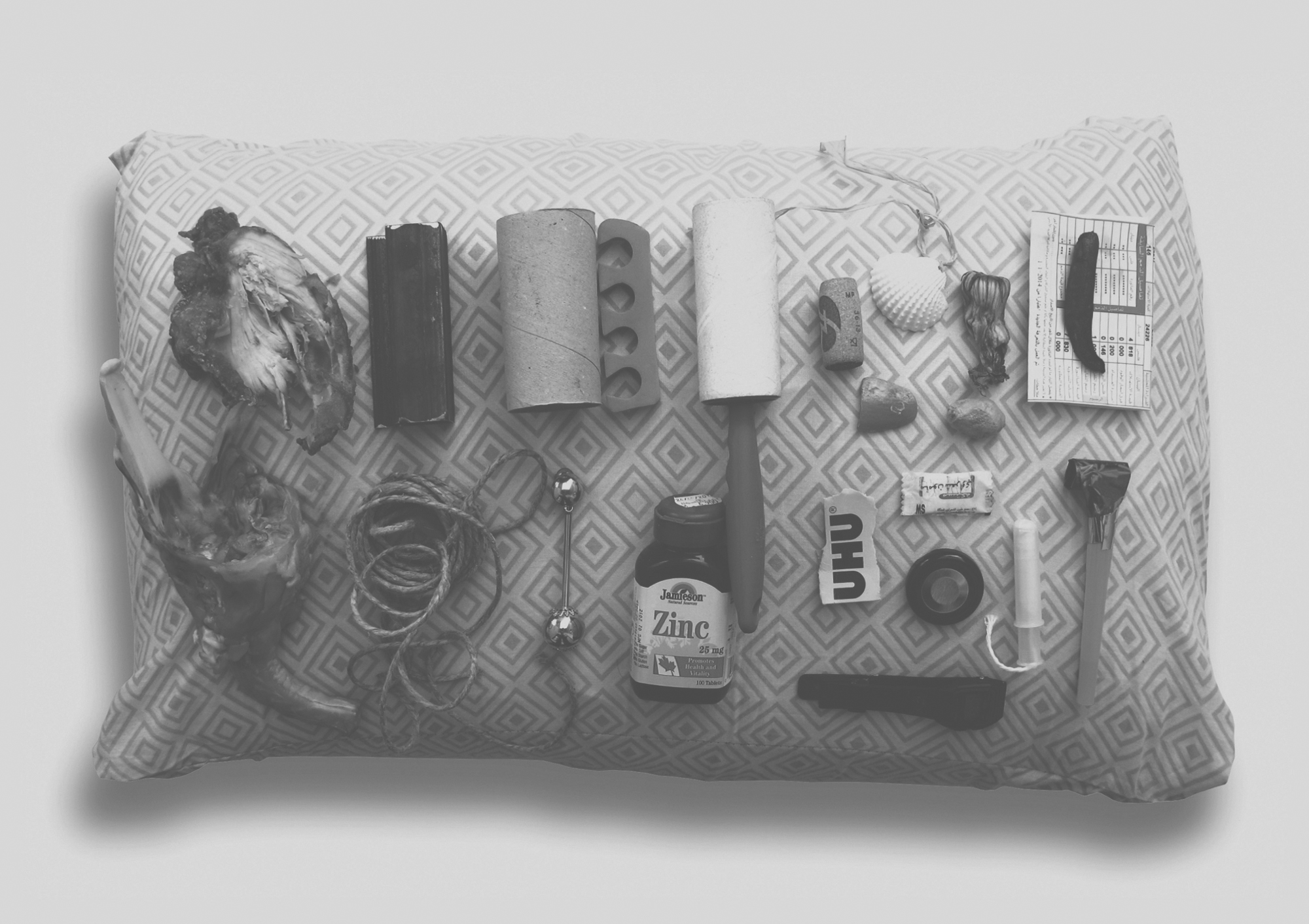

It’s Hind’s turn to speak. ‘I’m interested in dreams,’ she says. ‘And how we experience them as another type of existence, another world to live in.’ She shows us a picture on her phone. ‘It’s a pillow, and on it are various ingredients — lemons, garlic cloves, spices, whatever. By storing the pillow and the ingredients together, the one absorbs the others, and you can then control what kind of dream you have according to your desires.’

‘Thank God,’ says Yasser. ‘Something not about death!’ There is another ripple of laughter.

‘Actually,’ says Suzanne, ‘Sleep is sometimes known as “the little death.”’

‘Has anyone got anything not about death?’ asks Toleen.

'Collection of household objects which, when placed inside a pillow, are believed to affect events in the user’s dream world, and in turn life in the material world.’ (Hind Dabbagh)

They have: tribal markings and amulets; imaginary animal tracks; indecipherable archeological descriptions; jewellery that defies the laws of physics; superstitious body movements. With balance restored to this imaginary society, we’re ready to break so that they may begin the process of manifesting these ideas into artefacts.

Despite the initial preoccupation with death rituals there is no sense of morbidity within the walls of the King Ghazi Hotel, an abandoned space in bustling downtown Amman re-fitted for the purpose of the Spring Sessions. Here emerging artists arrive every day to engage with workshops designed to challenge and enable them to produce original artefacts. It’s a fast-paced experience in which anything goes and in which everything is explored, tested, iterated and then discussed over long dinners and parties on the roof.

‘The main thing we’re trying to achieve is to enable our participants,’ explains Noura al-Khasawneh who, in partnership with Toleen Touk, conceived the Spring Sessions. ‘It's a unique space away from the established art scene, a place to carry out all kinds of thought experiments.’ This reminds me of something Brian Eno once said, about art being a place in which we conduct experiments too dangerous for real life. ‘Exactly,’ says Noura.

︎

I have been invited here to explore with the group the opportunities for creating narratives via the production of material artefacts, and how a collection of seemingly unrelated fragments can paint a bigger picture of another time and place. The starting point for this is my own diagram ‘The Taxonomy of Lies’. A work in progress, the diagram is a fine-graded categorisation of approaches to narrative that explores the spaces between fiction and non-fiction, the implicit and the explicit. To illustrate the idea we look at a number of practitioners who have worked along similar lines: Donald Evans, the American artist who designed postage stamps for imaginary countries; Danish photographer Asger Carlsen, who makes documentary-style photographs of bizarre and impossible situations; The Beatles as Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; Jorge Luis Borges’ magic-realist Fictions; William Boyd’s Nat Tate conceit; Jeff de Boer’s mouse armour; Mingering Mike’s imaginary album covers.

To my surprise the artist who seems to generate the most interest amongst participants is Jessica Sue Layton, specifically her ‘Housesitting’ project. For ‘Housesitting’ Layton, as suggested in the title, volunteers to house-sit for people. Once she is alone in their homes, she observes the objects around her — the decor, the furnishings, the knick-knacks — and forms a picture in her mind of who these people are, their sense of identity as expressed by their possessions. She then dresses in their clothes and commissions a photographer to take her portrait ‘as’ the owner of the house. The final images — Jessica as Vanessa, as Susan, as Dr. Lucy Soutter — express how easily an imaginary world can be conjured from existing objects, and how easily we as viewers can slip into this space. It is also a way to question how we feel about the discomfiting aspects of certain types of conceit, and how these feelings might inform the kind of artefacts we want to make. The presentation ends with a quote from the British writer George MacDonald: ‘A man may, if he pleases, invent a little world of his own, with its own laws.’

On the rooftop of the King Ghazi Hotel posing for Deema Dabis' project exploring ideas of ritual movement.