Rats Constructing Labyrinths: Volume 2

Second volume collecting the experimental methods of MA Graphic Design students.

Editor, designer: Nicholas Jeeves

Contributors: Taiwo Dehinsilu, Jonathan Nicholson, Sarah Pooley

Digitally printed by Langham Press

Paperback

76pp

140mm x 210mm

Full colour

Ruskin Arts, 2025

Editor, designer: Nicholas Jeeves

Contributors: Taiwo Dehinsilu, Jonathan Nicholson, Sarah Pooley

Digitally printed by Langham Press

Paperback

76pp

140mm x 210mm

Full colour

Ruskin Arts, 2025

Introduction

1. A More Interesting Place

In Joe Fig’s Inside the Painter’s Studio (Princeton, 2009) the painter Chuck Close observes:

Forty years earlier, graduated from Yale and already acknowledged as an accomplished painter, the 27-year-old Close had asked himself just such a question: what if he abandoned his brushes and chose instead ‘to do things I had no facility with?’. It was a deeply counterintuitive move, but one that forced him to develop new methods of painting that would redefine his practice and, later, reinvigorate the world of portraiture. ‘A more interesting place’ indeed.

2. Means and Ends

For the newly-arrived MA Graphic Design student, an interesting question to start with might be: what is an MA for? Often the answer will pertain to ideas of refinement or excellence: the student has arrived with a portfolio containing some controlled and precise design work, and may expect on graduation to have refined it to the level of excellence.

It is perhaps a reasonable expectation, but it is not necessarily the function of an MA to enable students to design ever more controlled and precise outcomes; nor is it the case that increased control or precision will automatically confer the condition of excellence. The greater function of an MA (or at any rate, of our MA) is to develop in the student new ways of thinking and making: to expand frames of reference, to challenge creative habits and inclinations, to explore complex ideas they may not fully understand, to begin making more nuanced intellectual and imaginative connections, and to bring all these to bear on the perceived boundaries of design practice — their own, and of the design profession more widely.

For the project we call ‘Rats Constructing Labyrinths’ our students are invited to question not just the role, purpose and value of an MA, but of design and the designer. To do this they must first set aside the assumption that problem solving is the central concern of design and designers, and begin instead to engage with the more interesting business of problem creation.

The methods we use to explore ideas of problem creation — namely chance, constraint, disruption and automation — can at first be disorientating. Habitual design processes might be reliable but can quickly become engrained, and thereafter self-limiting; to challenge them, or to have them questioned as in some way being ‘wrong’, or at least insufficient, can throw a design student into disarray.

Often the more confident the designer the more profoundly this is felt. To some extent this is just as intended, but as we will discover in this book, these methods are not meant to replace established models of design thinking: rather, to provide an alternative perspective on means and ends.

Students begin this holiday from convention by reading, looking at and discussing some of the experimental methods used by figures from the worlds of literature, poetry, music and art. In other words: almost anything but graphic design.

This naturally raises the question of how such ideas might apply to graphic designers. It’s a fair question and, in the spirit of our course aims, one we carefully neglect to answer: it is what we are asking them, such that they might seek and find for themselves ‘a more interesting place’.

3. According to the Laws of Chance

In 1920 the poet Tristan Tzara published instructions on how to make a Dadaist poem:

When constructing his own poems using this method, Tzara found the process singularly rewarding, capable of producing such lines as:

(Bilan, 1919; translated from the French by Forrest Pelsue)

With Tzara’s method the poetic act is wrested from ideas of skill or creative self-expression and given over to the forces of chance. In consequence the poet finds that they are not so much writing a poem as encountering it.

The idea of the artist encountering rather than creating an artwork was central to the Dada movement. But it had already been circulating among the avant-garde for some time. A few years prior to the publication of Tzara’s instructions the painter Hans (later Jean) Arp had drawn on the power of chance to produce a pair of dynamic collages. Untitled with the parenthetical explanation ‘Squares Arranged According to the Law of Chance’, the collages consist of fragments of painted paper distributed across a surface, as though they had merely fallen into place. This, Arp claimed, was just what had occurred, his collages ‘arranged automatically, without will’.

The claim is enticing but not really convincing. While some of his later compositions do appear to be governed by chance, in these early examples there is a clear suggestion of order, of an artistic repositioning of the fragments made after the fact. Arp may not have fully ceded control during these experiments, but it doesn’t matter. For him drawing on methods of chance was a liberating action, a way of beginning that enabled him to temporarily sidestep his conscious mind and his artistic inclinations, and to obtain access to new creative territories.

It is a beguiling thought to play with: to temporarily surrender one’s talents to chance, resulting in artworks that might have been made by almost anyone. Yet we should not overlook the fact that both the invention of the method and the artist’s engagement with it as a process are in themselves creative acts. Moreover, artworks produced using such methods have the power to generate authentically original outcomes, resistant to anticipation or emulation. As such they have a huge capacity to surprise — a condition of key interest to the early Dadaists.

Another artist who has used chance to effect the condition of surprise is the printmaker Philippa Wood, most notably in the edition of twelve books titled Collage of Chance (Caseroom Press, 2021). Wood began this work by cutting a quantity of typographic prints into sections. These sections were then sequenced in the books using not aesthetic judgement but the throw of a dice.

By such means the power of chance is given agency in Wood’s books but, as with Arp’s collages, does not govern them completely. Before the sequencing could begin there would have been considerable calculation: defining the size of the book and the printed sections in relation to each other, and ensuring a sufficient quantity of sections for the number of editions planned — and after, once the sections had been assembled, some subtle adjustment.

Someone who has permitted chance to govern his work is Daniel Eatock. For an exhibition curated by the Japanese designer Akiko Kanna, Eatock was invited, along with thirteen others, to produce a poster. He responded not with a design but an instruction: to originate his poster by overprinting all thirteen posters contributed by the other invitees. The method was even to be applied to the poster’s title: it should be formed from the titles of all the other posters, in alphabetical order.

Being that at the time of his instruction the other posters had even to be conceived, Eatock could have had no way of anticipating what his poster would look like (or indeed be titled). It is a technique he has used more than once, with variable results. The question of whether or not such a deliberately disengaged approach is mitigated by the thinking behind it is debatable; whether it constitutes design at all, perhaps more so. (These are, of course, just the right kinds of questions for a postgraduate designer to grapple with.)

To demonstrate the role and value of chance-based operations in practice, our students were given a two-part assignment. For Assignment 1.1 they first cut a printed sheet into equally-sized fragments and then reassembled it, selecting each fragment randomly. For Assignment 1.2 they used viewfinders to crop areas of this reassemblage, using their critical judgement to identify any engaging secondary compositions contained within.

By such means, as with Hans Arp and Philippa Wood, our students were first using chance to initiate a piece of work, and later their judgement to identify interesting visual tensions and harmonies. Many of them were surprised to discover that some of the compositions they encountered were at least as innovative and as engaging as anything they might have produced consciously. The realisation of such a counterintuitive idea can be the moment in which a student begins to seriously question the unassailability of their design habits.

4. Departure Points

Chance is not the only means by which a creative might effect a radical change in their process: another is with the application of a carefully designed set of constraints.

Graphic designers are already quite familiar with the idea of working within constraints, whether these are imposed by a client (with type specifications and colour palettes defined by brand guidelines), by budget (working with a single colour to reduce the cost of printing, or to maximise the print run), or by themselves (designing to a mathematically structured grid or with a single typeface).

Constraints can be thought of as simple rules set out in advance: ‘you can do this, but not that.’ Such rules need not be limiting, and in practice are usually quite the opposite: a clearly defined set of constraints should automatically generate interesting complexities, which in turn can effect more inspired outcomes. The most familiar demonstration of this principle is the game of football, a creative activity with almost limitless scope for invention, improvisation and self-expression. But it is also played within an extensive and very tight set of constraints: the rules of the game that dictate the number of players, where the players can be at any given time, the boundaries of play, which parts of the body can be put to the ball, and so on. Without these rules there is no game at all: only a person in a field with a ball.

Gianfranco Contini — who sounds like a footballer but who was in fact a philologist — encapsulated this idea when he wrote in Varianti (Einaudi, 1970): ‘The departure point for inspiration is the obstacle’. He was writing about poetry and the formal structures of rhyme scheme, rhythm and metre. But the same principle applies to the achievement of almost any creative endeavour, be it football, falling in love, communing with God, or even designing a book. Constraints, Contini was saying, do not obstruct inspiration: they force it.

Of all the practitioners to have embraced the idea of using constraints as a means of provoking more interesting outcomes, it was the French interdisciplinary group Oulipo who embraced it most tightly. Founded in 1960, Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, or ‘workshop of potential literature’) was conceived as a loose formation consisting largely of writers, poets and mathematicians. Their thesis was that creative energies could be unleashed not by the application of chance or the unconscious but by rule-bound procedures and severe formal restrictions. Their objectives were, and remain, twofold: to identify or create useful literary constraints, and to produce original work that would demonstrate their potential in new and interesting ways.

Oulipan constraints include the ‘Snowball’, a poetic form in which each line is a single word, with each successive word one letter longer than the last. (Taiwo Dehinsilu demonstrates a prose variant of this with ‘Plus One’ in this book.) There is also the ‘Kick-Start’, in which every sentence in a text starts with the same phrase (for example, ‘I remember’, as in Joe Brainard’s mesmerising biography of the same name; again Taiwo takes up the challenge here). And perhaps most famously there is Jean Lescure’s ‘N+7’, which invites the author to replace each noun in a text with the seventh common noun that follows it in a dictionary. (An example of ‘N+12’ precedes this essay.)

It was Raymond Queneau, the co-founder of Oulipo, who described what they were doing as ‘rats constructing the labyrinths from which we plan to escape’. By concentrating their efforts on creating a method rather than an outcome, and then running that method to see what surprising results might be produced, the Oulipans were both rat and labyrinth-maker.

What this amounts to is that by inventing and developing such rigorous constraints the Oulipans were also inventing games: games intended to be adopted and adapted by others. One of the most astonishing exhibitions of these games was produced by the writer Georges Perec. Having identified the constraint known as the lipogram, a form of writing in which particular letters are avoided by the author, he demonstrated it by writing La disparition (the disappearance; Gallimard, 1969), a 300-page novel that does not contain the letter E — an almost unimaginable achievement being that E is the most common letter in French (as it is in English). He followed this in 1972 with Les Revenentes (the returned; Editions Julliard, 1972), a ‘univocal’ novella that uses no vowels except for E.

But it was Queneau himself who produced perhaps the most complex and visually alluring demonstration of Oulipan technique with A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (Gallimard, 1961). Aiming to construct a book of poems that could be read in multiple ways and thereby spawn multiple meanings, he proposed a collection of ten sonnets, with each line printed on a separate strip of card. To realise it Queneau would need the help of both a mathematician (Francois Le Lionnais) and a designer (Robert Massin). The outcome is a marvel of applied thought, with the turning of each strip producing a new permutation of the sonnet in view. Turning all the strips in combination would create a quadrillion different permutations. To put that number into context, it is estimated that to read every permutation would take more than 200 million years.

The idea of the Oulipan constraint can be modulated to suit almost any creative discipline, and since the formation of Oulipo there have emerged a number of offshoots that concern themselves exclusively with aspects of the visual arts, including Oubapo (for comics); Oupeinpo (painting); Ouphopo (photography); Oucarpo (cartography); and Ougrapo (graphic design). To test our students’ potential for Outypo membership, they embarked on their next set of studio assignments. For these they explored the effects on the design process of applying both time-based and material constraints.

For Assignment 2.1, students were invited to cut a letter T of their own design from card within ten seconds. For Assignment 2.2 they were asked to cut a second letter T, this time taking exactly ten minutes and with the scissors cutting at all times. For Assignment 2.3 the constraint was solely material: tearing a letter (in Clarendon Bold Condensed) by hand.

In each case it is the perceived inappropriateness and inconvenience of the method that has led to such interesting and unpractised results. There is no sense that one outcome is ‘better’ than another; each has its own qualities determined by the circumstances of its making.

5. Breaking Habits

Of all the methods our students would explore for this project, disruption has perhaps the greatest capacity to transform an individual talent. But it can also be the most unnerving, the most counterintuitive, and the most productive — which might tell us something about what these conditions have in common.

Notable proponents of disruption as a creative methodology are Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, whose Oblique Strategies remain the wellspring for creatives seeking to surprise themselves. Taking the form of a deck of printed cards, the Strategies provide a series of enigmatic instructions for the artist to integrate into their work. This can be achieved in two ways. The first is for the artist to draw a card at random before commencing a piece of work, and use the instruction found there to disrupt their usual creative impulses. The second is for the artist to work just as they always have, and having produced an outcome, to then disrupt it by drawing a card and applying the instruction, iterating the work towards something radically different. As Eno explained in 1980:

By applying the Oblique Strategies to their process the artist is forced to set aside their habitual creative tendencies and with them their inherent limitations. The very obliqueness of the strategies (‘Abandon normal instruments’; ‘Don’t stress one thing more than another’; ‘Do nothing for as long as possible’) ensure that the individual designer — or painter, sculptor, musician or dancer — can interpret their instruction within the context of their practice.

To experiment with some strategic disruption of their own, for Assignment 3.1 our students enacted an interpretation of the instruction ‘Only one element of each kind’. Working in pairs, one designer (or element) would control a computer keyboard and attempt to type a supplied text (in this instance the UK national anthem). Meanwhile the other designer would frustrate this attempt by manipulating the mouse and clicking on-screen commands at will. Communication during this process was prohibited.

The results of these experiments were printed out and, for Assignment 3.2, again subjected to some critical judgement with the viewfinders. The final outcomes are as lively and as interesting as anything that might have been produced by ‘head-on’ approaches, and could be viewed either as speculative artworks in themselves or as starting points for more consciously developed designs.

Despite the evidence of these successes none of our students wished to revisit or reinterpret this method for their own projects. Relinquishing control to the limitations imposed by chance or constraint is, perhaps, one thing; to submit to the disruptive will of another human being quite something else. Being that such a process feels like such an anti-collaborative act — inviting another to spoil one’s good intentions — it may be too counterintuitive a process for many designers to countenance.

Still, a project like Alain Robbe-Grillet and Robert Rauschenberg’s book Traces Suspectes en Surface (or Things Are Not What They Seem; ULAE, 1978) provides thrilling evidence of what such methods can achieve. Not so much a collaboration as a creative conversation — or possibly an argument — conducted over six years, Robbe-Grillet would first inscribe his text directly onto lithographic plates. These were then sent to Rauschenberg, who responded by imposing his photographic collages. Robbe-Grillet apparently gave little or no consideration to Rauschenberg’s intentions or requirements when setting out his texts; the book’s dissonances as a result are a key component of its beauty.

6. Where There is Data

In 2017 the designers Muir McNeil were invited to design the cover for issue 94 of Eye magazine. They responded by proposing not one cover but 8000 different covers — one for every reader.

Self-evidently, designing 8000 individual covers is not something that can be achieved within a reasonable timescale or budget. But for Eye 94 Muir McNeil were using Mosaic, a digital print system that allows designers to automate part of the design process.

The idea, if not the technology that enables it, is quite simple. The designer first creates one or more complex ‘seed images’. The system then takes these images and, to a set of parameters defined by the operator, crops, scales and rotates small sections of them to generate new compositions. The process is very similar to our students’ use of the viewfinders in their first assignments. But in the case of Eye 94 the resulting compositions had to be both sufficiently detailed to bear being scaled up to the size of a magazine cover, and sufficiently engaging to impress a very design-literate readership. Correspondingly the larger and more detailed the seed image, the greater the number of individually distinctive designs that can be extracted from it. It is a technology that brands such as Coca-Cola, Nutella and Smirnoff have since used to considerable effect, enabling consumers to purchase uniquely labelled examples of their favourite products (and thereby making them feel profitably special).

Automating a part of the design process in this way again challenges how we might understand ‘creativity’. But again, as with all of the methods discussed in this book, both the design of the system and the designer’s engagement with it as a process are legitimately creative acts. In order to exploit technologies like Mosaic to satisfactory ends, the designer is first required to see their potential. Thereafter they must experiment with the design and the density of the seed images, and test the effectiveness of the parameters they have input. A failing in any of these areas will produce defective results, requiring a rethink of the seed image design and the operating parameters, and triggering another sequence of tests.

The use of algorithms as a means of producing images is not a 21st century idea. In the early 1960s Georg Nees pioneered the use of computer coding to produce some of the earliest examples of what we now call generative art. By writing a series of code libraries and sending these to a mechanical plotter, Nees found that he could produce drawings in which the artist’s hand played only a supporting role. To some critics this may have felt like cheating, but given a moment’s thought, it is no more cheating than using a camera obscura or a pantograph — both tools employed by Renaissance artists and craftsmen.

Nees first exhibited his generative images in Stuttgart in 1965. For the show’s title he coined a phrase now very familiar to us: Computergrafik. What Nees’ computer graphics have in common with the designs generated by the application of tools like Mosaic (and indeed methods of chance, constraint and disruption) is that there was no practical way for him to anticipate the appearance of an artwork before it had been created.

More recently Brian Eno (he of the Oblique Strategies) has used similar technologies to make 77 Million Paintings. A screen-based art installation, the work consists of a hypnotic sequence of unrepeated music and visuals. The figure of 77 million is merely a euphonious title; the number of permutations has varied as Eno has adapted and relocated it, perhaps most memorably on the sails of Sydney Opera House.

With the development of computer technology, including AI, we have since witnessed the rise of Art Blocks, a virtual gallery for generative art conceived by Erick Calderon, a former ceramic tile merchant. Artists upload their creative code to Art Blocks and, when a collector purchases an artwork (sight unseen, as it doesn’t yet exist) they trigger the creation of a new iteration in the form of an NFT — a ‘non-fungible token’, or purely digital image. Whereas generative artists like Georg Nees would run their algorithms and select only the best iterations for exhibition, with Art Blocks the artist and buyer both accept whatever is generated by the code. Says Calderon: ‘Because Art Blocks forces the artist to accept every single output of the algorithm as a signed piece, the artist has to tweak the algorithm until it’s perfect: they can’t just cherry-pick the good outputs.’ The number of outputs is capped in simulation of the editioned print, and all trading takes place using cryptocurrency. In the world of computer-generated NFTs, not even the money is real.

An increasing number of design and branding agencies (who are profoundly interested in real money) are now exploring the power of coding to generate work for their clients. The generative designer Patrik Hübner, whose motto is ‘Where there is data there is design’, has developed intuitively operated software systems that both his design team and his clients can use to generate volumes of on-brand graphics from a fixed set of visual assets. The results are playful and often quite engaging, and the technology makes the designer-client relationship a much more agile one. It might also be argued that it makes the relationship much less intimate, but whether or not this is what a client or a designer want for each other is for the 21st century design student to work out.

In the meantime, to experience something of this way of working for themselves, our students were invited to participate in Assignment 4.1 — a collaborative method of graphic production we call ‘Adding, Adjusting, Taking Away’. Working in Adobe Illustrator, participants were provided with a blank artboard and, adjacent to it, a set of visual assets. Taking it in turns, the students could either add an asset to the board, adjust an asset previously placed there, or take one away.

In running this assignment we find that, almost without exception, a pattern of behaviour soon emerges. First there is the sustained adding and layering of assets — partly out of an enthusiasm for building, but also out of a polite reluctance to delete the additions of others. Next, that reluctance is overcome as the students become more confident and begin a phase of playful de-cluttering. Finally, an unspoken direction for the image starts to materialise, in which all participants seem to be moving towards a kind of intuitively agreed design vision. The composition is fixed, and the activity ends, when any one student declares the artwork complete.

7. Setting a Scene

Perceptive young designers will notice that there can be considerable overlap in methods of chance, constraint, disruption and automation. The ‘Adding, Adjusting, Taking Away’ assignment, for example, is inspired by an automated process — but the designers are also constrained by a limited palette of visual assets, and have their desires and intentions disrupted by the actions of others. Similarly the disruptive Oblique Strategy ‘Work at a different speed’ might be selected from the deck by chance, but it pertains to a time-based constraint.

Still, in whatever manner the work is generated, it is the artist who must set the conditions for its production and who must thereby determine the rules. In this sense their task is akin to a director setting the scene for an improvised performance: what happens once the players arrive and begin interacting is not exactly controlled, but rather observed and assessed. If necessary there may be tactful corrections, but if what happens is not working at all, the scene may be struck or re-set, and a new cycle of activity begun. In the end, what all the participants are trying to effect is an encounter with an unnamed something — a force, a charge, a spark of interest that may be identified, explored and developed.

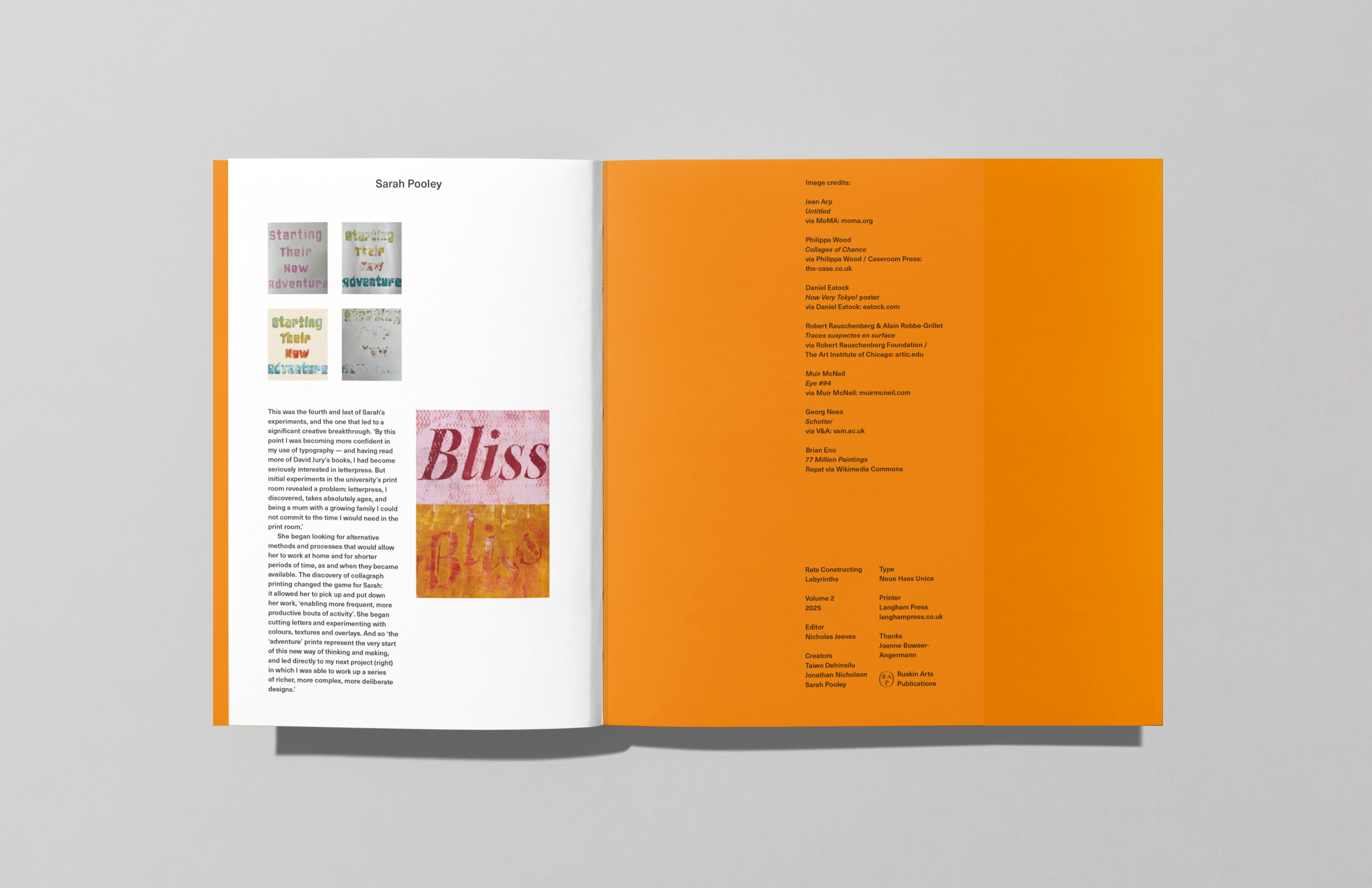

Such are the questions — of means and ends, of methods and ideas — that our MA Graphic Design students were invited to engage with for the production of this book. To initiate the process they were first prescribed a series of methods for generating texts. The completed texts were then passed to another student, or sometimes (due to a randomised method of their own devising) back to themselves. From there the second student would invent and deploy a chance-, constraint-, disruption- or automation-based method for generating original typographic visuals.

The layout of this book gives equal value to all their outputs, whether text, methodology, or visual. This is just as it should be, for each output is a formulation of an answer. Some of these answers are assured and some more tentative.

In any case they have in turn provoked a rapid branching of yet more interesting questions, such as: what is an idea? What is creativity? What are mistakes? And perhaps most interesting of all: what is a graphic designer? In taking on this work they have opened up new intellectual and imaginative pathways, we hope leading to ‘more interesting places’. What they might find in these places, and how they respond, will determine the kind of designer they become.

In Joe Fig’s Inside the Painter’s Studio (Princeton, 2009) the painter Chuck Close observes:

‘We are much too problem-solving oriented. It is far more interesting to participate in problem creation. Ask yourself an interesting enough question and you will soon find yourself in a more interesting place.’

Forty years earlier, graduated from Yale and already acknowledged as an accomplished painter, the 27-year-old Close had asked himself just such a question: what if he abandoned his brushes and chose instead ‘to do things I had no facility with?’. It was a deeply counterintuitive move, but one that forced him to develop new methods of painting that would redefine his practice and, later, reinvigorate the world of portraiture. ‘A more interesting place’ indeed.

2. Means and Ends

For the newly-arrived MA Graphic Design student, an interesting question to start with might be: what is an MA for? Often the answer will pertain to ideas of refinement or excellence: the student has arrived with a portfolio containing some controlled and precise design work, and may expect on graduation to have refined it to the level of excellence.

It is perhaps a reasonable expectation, but it is not necessarily the function of an MA to enable students to design ever more controlled and precise outcomes; nor is it the case that increased control or precision will automatically confer the condition of excellence. The greater function of an MA (or at any rate, of our MA) is to develop in the student new ways of thinking and making: to expand frames of reference, to challenge creative habits and inclinations, to explore complex ideas they may not fully understand, to begin making more nuanced intellectual and imaginative connections, and to bring all these to bear on the perceived boundaries of design practice — their own, and of the design profession more widely.

For the project we call ‘Rats Constructing Labyrinths’ our students are invited to question not just the role, purpose and value of an MA, but of design and the designer. To do this they must first set aside the assumption that problem solving is the central concern of design and designers, and begin instead to engage with the more interesting business of problem creation.

The methods we use to explore ideas of problem creation — namely chance, constraint, disruption and automation — can at first be disorientating. Habitual design processes might be reliable but can quickly become engrained, and thereafter self-limiting; to challenge them, or to have them questioned as in some way being ‘wrong’, or at least insufficient, can throw a design student into disarray.

Often the more confident the designer the more profoundly this is felt. To some extent this is just as intended, but as we will discover in this book, these methods are not meant to replace established models of design thinking: rather, to provide an alternative perspective on means and ends.

Students begin this holiday from convention by reading, looking at and discussing some of the experimental methods used by figures from the worlds of literature, poetry, music and art. In other words: almost anything but graphic design.

This naturally raises the question of how such ideas might apply to graphic designers. It’s a fair question and, in the spirit of our course aims, one we carefully neglect to answer: it is what we are asking them, such that they might seek and find for themselves ‘a more interesting place’.

3. According to the Laws of Chance

In 1920 the poet Tristan Tzara published instructions on how to make a Dadaist poem:

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

The poem will be like you.

And here are you a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming, though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.

When constructing his own poems using this method, Tzara found the process singularly rewarding, capable of producing such lines as:

near the heart

we note the black shivers under a lens

is this feeling this white spouting

and methodical love

splits my body into rays

toothpaste pastry

(Bilan, 1919; translated from the French by Forrest Pelsue)

With Tzara’s method the poetic act is wrested from ideas of skill or creative self-expression and given over to the forces of chance. In consequence the poet finds that they are not so much writing a poem as encountering it.

The idea of the artist encountering rather than creating an artwork was central to the Dada movement. But it had already been circulating among the avant-garde for some time. A few years prior to the publication of Tzara’s instructions the painter Hans (later Jean) Arp had drawn on the power of chance to produce a pair of dynamic collages. Untitled with the parenthetical explanation ‘Squares Arranged According to the Law of Chance’, the collages consist of fragments of painted paper distributed across a surface, as though they had merely fallen into place. This, Arp claimed, was just what had occurred, his collages ‘arranged automatically, without will’.

The claim is enticing but not really convincing. While some of his later compositions do appear to be governed by chance, in these early examples there is a clear suggestion of order, of an artistic repositioning of the fragments made after the fact. Arp may not have fully ceded control during these experiments, but it doesn’t matter. For him drawing on methods of chance was a liberating action, a way of beginning that enabled him to temporarily sidestep his conscious mind and his artistic inclinations, and to obtain access to new creative territories.

It is a beguiling thought to play with: to temporarily surrender one’s talents to chance, resulting in artworks that might have been made by almost anyone. Yet we should not overlook the fact that both the invention of the method and the artist’s engagement with it as a process are in themselves creative acts. Moreover, artworks produced using such methods have the power to generate authentically original outcomes, resistant to anticipation or emulation. As such they have a huge capacity to surprise — a condition of key interest to the early Dadaists.

Another artist who has used chance to effect the condition of surprise is the printmaker Philippa Wood, most notably in the edition of twelve books titled Collage of Chance (Caseroom Press, 2021). Wood began this work by cutting a quantity of typographic prints into sections. These sections were then sequenced in the books using not aesthetic judgement but the throw of a dice.

By such means the power of chance is given agency in Wood’s books but, as with Arp’s collages, does not govern them completely. Before the sequencing could begin there would have been considerable calculation: defining the size of the book and the printed sections in relation to each other, and ensuring a sufficient quantity of sections for the number of editions planned — and after, once the sections had been assembled, some subtle adjustment.

Someone who has permitted chance to govern his work is Daniel Eatock. For an exhibition curated by the Japanese designer Akiko Kanna, Eatock was invited, along with thirteen others, to produce a poster. He responded not with a design but an instruction: to originate his poster by overprinting all thirteen posters contributed by the other invitees. The method was even to be applied to the poster’s title: it should be formed from the titles of all the other posters, in alphabetical order.

Being that at the time of his instruction the other posters had even to be conceived, Eatock could have had no way of anticipating what his poster would look like (or indeed be titled). It is a technique he has used more than once, with variable results. The question of whether or not such a deliberately disengaged approach is mitigated by the thinking behind it is debatable; whether it constitutes design at all, perhaps more so. (These are, of course, just the right kinds of questions for a postgraduate designer to grapple with.)

To demonstrate the role and value of chance-based operations in practice, our students were given a two-part assignment. For Assignment 1.1 they first cut a printed sheet into equally-sized fragments and then reassembled it, selecting each fragment randomly. For Assignment 1.2 they used viewfinders to crop areas of this reassemblage, using their critical judgement to identify any engaging secondary compositions contained within.

By such means, as with Hans Arp and Philippa Wood, our students were first using chance to initiate a piece of work, and later their judgement to identify interesting visual tensions and harmonies. Many of them were surprised to discover that some of the compositions they encountered were at least as innovative and as engaging as anything they might have produced consciously. The realisation of such a counterintuitive idea can be the moment in which a student begins to seriously question the unassailability of their design habits.

4. Departure Points

Chance is not the only means by which a creative might effect a radical change in their process: another is with the application of a carefully designed set of constraints.

Graphic designers are already quite familiar with the idea of working within constraints, whether these are imposed by a client (with type specifications and colour palettes defined by brand guidelines), by budget (working with a single colour to reduce the cost of printing, or to maximise the print run), or by themselves (designing to a mathematically structured grid or with a single typeface).

Constraints can be thought of as simple rules set out in advance: ‘you can do this, but not that.’ Such rules need not be limiting, and in practice are usually quite the opposite: a clearly defined set of constraints should automatically generate interesting complexities, which in turn can effect more inspired outcomes. The most familiar demonstration of this principle is the game of football, a creative activity with almost limitless scope for invention, improvisation and self-expression. But it is also played within an extensive and very tight set of constraints: the rules of the game that dictate the number of players, where the players can be at any given time, the boundaries of play, which parts of the body can be put to the ball, and so on. Without these rules there is no game at all: only a person in a field with a ball.

Gianfranco Contini — who sounds like a footballer but who was in fact a philologist — encapsulated this idea when he wrote in Varianti (Einaudi, 1970): ‘The departure point for inspiration is the obstacle’. He was writing about poetry and the formal structures of rhyme scheme, rhythm and metre. But the same principle applies to the achievement of almost any creative endeavour, be it football, falling in love, communing with God, or even designing a book. Constraints, Contini was saying, do not obstruct inspiration: they force it.

Of all the practitioners to have embraced the idea of using constraints as a means of provoking more interesting outcomes, it was the French interdisciplinary group Oulipo who embraced it most tightly. Founded in 1960, Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, or ‘workshop of potential literature’) was conceived as a loose formation consisting largely of writers, poets and mathematicians. Their thesis was that creative energies could be unleashed not by the application of chance or the unconscious but by rule-bound procedures and severe formal restrictions. Their objectives were, and remain, twofold: to identify or create useful literary constraints, and to produce original work that would demonstrate their potential in new and interesting ways.

Oulipan constraints include the ‘Snowball’, a poetic form in which each line is a single word, with each successive word one letter longer than the last. (Taiwo Dehinsilu demonstrates a prose variant of this with ‘Plus One’ in this book.) There is also the ‘Kick-Start’, in which every sentence in a text starts with the same phrase (for example, ‘I remember’, as in Joe Brainard’s mesmerising biography of the same name; again Taiwo takes up the challenge here). And perhaps most famously there is Jean Lescure’s ‘N+7’, which invites the author to replace each noun in a text with the seventh common noun that follows it in a dictionary. (An example of ‘N+12’ precedes this essay.)

It was Raymond Queneau, the co-founder of Oulipo, who described what they were doing as ‘rats constructing the labyrinths from which we plan to escape’. By concentrating their efforts on creating a method rather than an outcome, and then running that method to see what surprising results might be produced, the Oulipans were both rat and labyrinth-maker.

What this amounts to is that by inventing and developing such rigorous constraints the Oulipans were also inventing games: games intended to be adopted and adapted by others. One of the most astonishing exhibitions of these games was produced by the writer Georges Perec. Having identified the constraint known as the lipogram, a form of writing in which particular letters are avoided by the author, he demonstrated it by writing La disparition (the disappearance; Gallimard, 1969), a 300-page novel that does not contain the letter E — an almost unimaginable achievement being that E is the most common letter in French (as it is in English). He followed this in 1972 with Les Revenentes (the returned; Editions Julliard, 1972), a ‘univocal’ novella that uses no vowels except for E.

But it was Queneau himself who produced perhaps the most complex and visually alluring demonstration of Oulipan technique with A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (Gallimard, 1961). Aiming to construct a book of poems that could be read in multiple ways and thereby spawn multiple meanings, he proposed a collection of ten sonnets, with each line printed on a separate strip of card. To realise it Queneau would need the help of both a mathematician (Francois Le Lionnais) and a designer (Robert Massin). The outcome is a marvel of applied thought, with the turning of each strip producing a new permutation of the sonnet in view. Turning all the strips in combination would create a quadrillion different permutations. To put that number into context, it is estimated that to read every permutation would take more than 200 million years.

The idea of the Oulipan constraint can be modulated to suit almost any creative discipline, and since the formation of Oulipo there have emerged a number of offshoots that concern themselves exclusively with aspects of the visual arts, including Oubapo (for comics); Oupeinpo (painting); Ouphopo (photography); Oucarpo (cartography); and Ougrapo (graphic design). To test our students’ potential for Outypo membership, they embarked on their next set of studio assignments. For these they explored the effects on the design process of applying both time-based and material constraints.

For Assignment 2.1, students were invited to cut a letter T of their own design from card within ten seconds. For Assignment 2.2 they were asked to cut a second letter T, this time taking exactly ten minutes and with the scissors cutting at all times. For Assignment 2.3 the constraint was solely material: tearing a letter (in Clarendon Bold Condensed) by hand.

In each case it is the perceived inappropriateness and inconvenience of the method that has led to such interesting and unpractised results. There is no sense that one outcome is ‘better’ than another; each has its own qualities determined by the circumstances of its making.

5. Breaking Habits

Of all the methods our students would explore for this project, disruption has perhaps the greatest capacity to transform an individual talent. But it can also be the most unnerving, the most counterintuitive, and the most productive — which might tell us something about what these conditions have in common.

Notable proponents of disruption as a creative methodology are Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, whose Oblique Strategies remain the wellspring for creatives seeking to surprise themselves. Taking the form of a deck of printed cards, the Strategies provide a series of enigmatic instructions for the artist to integrate into their work. This can be achieved in two ways. The first is for the artist to draw a card at random before commencing a piece of work, and use the instruction found there to disrupt their usual creative impulses. The second is for the artist to work just as they always have, and having produced an outcome, to then disrupt it by drawing a card and applying the instruction, iterating the work towards something radically different. As Eno explained in 1980:

‘The Oblique Strategies evolved from me being in a number of working situations when the panic of the situation — particularly in studios — tended to make me quickly forget that there were others ways of working, and that there were tangential ways of attacking problems that were in many senses more interesting than the direct, head-on approach. If you’re in a panic, you tend to take the head-on approach because it seems to be the one that’s going to yield the best results. Of course, that often isn’t the case: it’s just the most obvious and — apparently — reliable method. The function of the Oblique Strategies was, initially, to serve as a series of prompts which said, “Don’t forget that you could adopt this attitude,” or “Don’t forget you could adopt that attitude.”’

By applying the Oblique Strategies to their process the artist is forced to set aside their habitual creative tendencies and with them their inherent limitations. The very obliqueness of the strategies (‘Abandon normal instruments’; ‘Don’t stress one thing more than another’; ‘Do nothing for as long as possible’) ensure that the individual designer — or painter, sculptor, musician or dancer — can interpret their instruction within the context of their practice.

To experiment with some strategic disruption of their own, for Assignment 3.1 our students enacted an interpretation of the instruction ‘Only one element of each kind’. Working in pairs, one designer (or element) would control a computer keyboard and attempt to type a supplied text (in this instance the UK national anthem). Meanwhile the other designer would frustrate this attempt by manipulating the mouse and clicking on-screen commands at will. Communication during this process was prohibited.

The results of these experiments were printed out and, for Assignment 3.2, again subjected to some critical judgement with the viewfinders. The final outcomes are as lively and as interesting as anything that might have been produced by ‘head-on’ approaches, and could be viewed either as speculative artworks in themselves or as starting points for more consciously developed designs.

Despite the evidence of these successes none of our students wished to revisit or reinterpret this method for their own projects. Relinquishing control to the limitations imposed by chance or constraint is, perhaps, one thing; to submit to the disruptive will of another human being quite something else. Being that such a process feels like such an anti-collaborative act — inviting another to spoil one’s good intentions — it may be too counterintuitive a process for many designers to countenance.

Still, a project like Alain Robbe-Grillet and Robert Rauschenberg’s book Traces Suspectes en Surface (or Things Are Not What They Seem; ULAE, 1978) provides thrilling evidence of what such methods can achieve. Not so much a collaboration as a creative conversation — or possibly an argument — conducted over six years, Robbe-Grillet would first inscribe his text directly onto lithographic plates. These were then sent to Rauschenberg, who responded by imposing his photographic collages. Robbe-Grillet apparently gave little or no consideration to Rauschenberg’s intentions or requirements when setting out his texts; the book’s dissonances as a result are a key component of its beauty.

6. Where There is Data

In 2017 the designers Muir McNeil were invited to design the cover for issue 94 of Eye magazine. They responded by proposing not one cover but 8000 different covers — one for every reader.

Self-evidently, designing 8000 individual covers is not something that can be achieved within a reasonable timescale or budget. But for Eye 94 Muir McNeil were using Mosaic, a digital print system that allows designers to automate part of the design process.

The idea, if not the technology that enables it, is quite simple. The designer first creates one or more complex ‘seed images’. The system then takes these images and, to a set of parameters defined by the operator, crops, scales and rotates small sections of them to generate new compositions. The process is very similar to our students’ use of the viewfinders in their first assignments. But in the case of Eye 94 the resulting compositions had to be both sufficiently detailed to bear being scaled up to the size of a magazine cover, and sufficiently engaging to impress a very design-literate readership. Correspondingly the larger and more detailed the seed image, the greater the number of individually distinctive designs that can be extracted from it. It is a technology that brands such as Coca-Cola, Nutella and Smirnoff have since used to considerable effect, enabling consumers to purchase uniquely labelled examples of their favourite products (and thereby making them feel profitably special).

Automating a part of the design process in this way again challenges how we might understand ‘creativity’. But again, as with all of the methods discussed in this book, both the design of the system and the designer’s engagement with it as a process are legitimately creative acts. In order to exploit technologies like Mosaic to satisfactory ends, the designer is first required to see their potential. Thereafter they must experiment with the design and the density of the seed images, and test the effectiveness of the parameters they have input. A failing in any of these areas will produce defective results, requiring a rethink of the seed image design and the operating parameters, and triggering another sequence of tests.

The use of algorithms as a means of producing images is not a 21st century idea. In the early 1960s Georg Nees pioneered the use of computer coding to produce some of the earliest examples of what we now call generative art. By writing a series of code libraries and sending these to a mechanical plotter, Nees found that he could produce drawings in which the artist’s hand played only a supporting role. To some critics this may have felt like cheating, but given a moment’s thought, it is no more cheating than using a camera obscura or a pantograph — both tools employed by Renaissance artists and craftsmen.

Nees first exhibited his generative images in Stuttgart in 1965. For the show’s title he coined a phrase now very familiar to us: Computergrafik. What Nees’ computer graphics have in common with the designs generated by the application of tools like Mosaic (and indeed methods of chance, constraint and disruption) is that there was no practical way for him to anticipate the appearance of an artwork before it had been created.

More recently Brian Eno (he of the Oblique Strategies) has used similar technologies to make 77 Million Paintings. A screen-based art installation, the work consists of a hypnotic sequence of unrepeated music and visuals. The figure of 77 million is merely a euphonious title; the number of permutations has varied as Eno has adapted and relocated it, perhaps most memorably on the sails of Sydney Opera House.

With the development of computer technology, including AI, we have since witnessed the rise of Art Blocks, a virtual gallery for generative art conceived by Erick Calderon, a former ceramic tile merchant. Artists upload their creative code to Art Blocks and, when a collector purchases an artwork (sight unseen, as it doesn’t yet exist) they trigger the creation of a new iteration in the form of an NFT — a ‘non-fungible token’, or purely digital image. Whereas generative artists like Georg Nees would run their algorithms and select only the best iterations for exhibition, with Art Blocks the artist and buyer both accept whatever is generated by the code. Says Calderon: ‘Because Art Blocks forces the artist to accept every single output of the algorithm as a signed piece, the artist has to tweak the algorithm until it’s perfect: they can’t just cherry-pick the good outputs.’ The number of outputs is capped in simulation of the editioned print, and all trading takes place using cryptocurrency. In the world of computer-generated NFTs, not even the money is real.

An increasing number of design and branding agencies (who are profoundly interested in real money) are now exploring the power of coding to generate work for their clients. The generative designer Patrik Hübner, whose motto is ‘Where there is data there is design’, has developed intuitively operated software systems that both his design team and his clients can use to generate volumes of on-brand graphics from a fixed set of visual assets. The results are playful and often quite engaging, and the technology makes the designer-client relationship a much more agile one. It might also be argued that it makes the relationship much less intimate, but whether or not this is what a client or a designer want for each other is for the 21st century design student to work out.

In the meantime, to experience something of this way of working for themselves, our students were invited to participate in Assignment 4.1 — a collaborative method of graphic production we call ‘Adding, Adjusting, Taking Away’. Working in Adobe Illustrator, participants were provided with a blank artboard and, adjacent to it, a set of visual assets. Taking it in turns, the students could either add an asset to the board, adjust an asset previously placed there, or take one away.

In running this assignment we find that, almost without exception, a pattern of behaviour soon emerges. First there is the sustained adding and layering of assets — partly out of an enthusiasm for building, but also out of a polite reluctance to delete the additions of others. Next, that reluctance is overcome as the students become more confident and begin a phase of playful de-cluttering. Finally, an unspoken direction for the image starts to materialise, in which all participants seem to be moving towards a kind of intuitively agreed design vision. The composition is fixed, and the activity ends, when any one student declares the artwork complete.

7. Setting a Scene

Perceptive young designers will notice that there can be considerable overlap in methods of chance, constraint, disruption and automation. The ‘Adding, Adjusting, Taking Away’ assignment, for example, is inspired by an automated process — but the designers are also constrained by a limited palette of visual assets, and have their desires and intentions disrupted by the actions of others. Similarly the disruptive Oblique Strategy ‘Work at a different speed’ might be selected from the deck by chance, but it pertains to a time-based constraint.

Still, in whatever manner the work is generated, it is the artist who must set the conditions for its production and who must thereby determine the rules. In this sense their task is akin to a director setting the scene for an improvised performance: what happens once the players arrive and begin interacting is not exactly controlled, but rather observed and assessed. If necessary there may be tactful corrections, but if what happens is not working at all, the scene may be struck or re-set, and a new cycle of activity begun. In the end, what all the participants are trying to effect is an encounter with an unnamed something — a force, a charge, a spark of interest that may be identified, explored and developed.

Such are the questions — of means and ends, of methods and ideas — that our MA Graphic Design students were invited to engage with for the production of this book. To initiate the process they were first prescribed a series of methods for generating texts. The completed texts were then passed to another student, or sometimes (due to a randomised method of their own devising) back to themselves. From there the second student would invent and deploy a chance-, constraint-, disruption- or automation-based method for generating original typographic visuals.

The layout of this book gives equal value to all their outputs, whether text, methodology, or visual. This is just as it should be, for each output is a formulation of an answer. Some of these answers are assured and some more tentative.

In any case they have in turn provoked a rapid branching of yet more interesting questions, such as: what is an idea? What is creativity? What are mistakes? And perhaps most interesting of all: what is a graphic designer? In taking on this work they have opened up new intellectual and imaginative pathways, we hope leading to ‘more interesting places’. What they might find in these places, and how they respond, will determine the kind of designer they become.